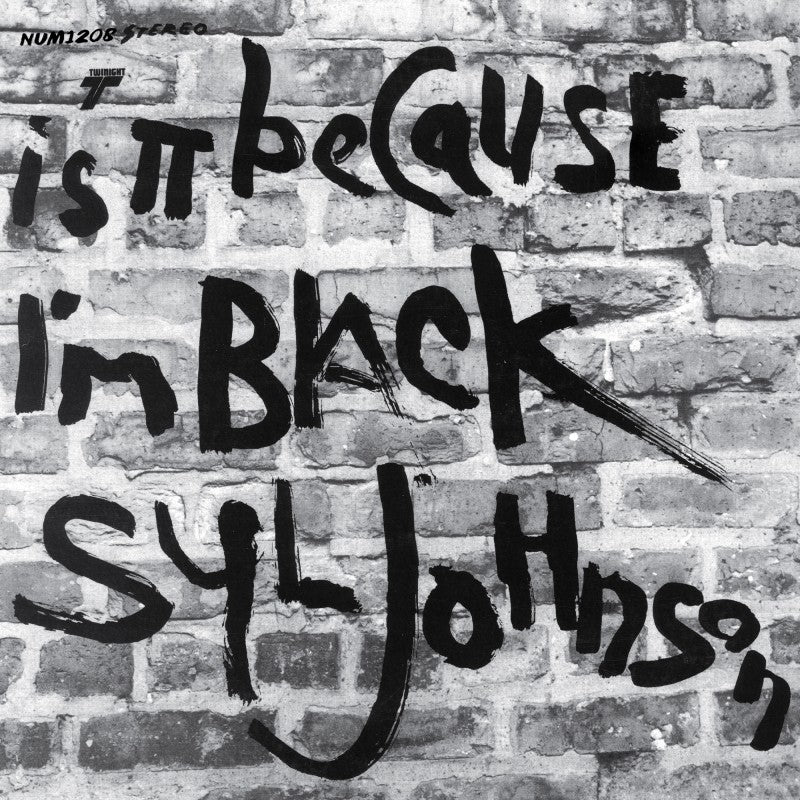

Syl Johnson - Is It Because I'm Black (180g, 50th Anniversary Edition)

Precio habitual

$ 660.00 MXN

Precio habitual

$ 750.00 MXN

Precio de oferta

$ 660.00 MXN

Precio unitario

/

por

Impuesto incluido.

No se pudo cargar la disponibilidad de retiro

Ten years into his role as poster boy for pop soul and peak-hour R&B, Syl Johnson did an unlikely about-face and cut his most inspiring and powerful album. The title track, coupled with the politically charged “I’m Talking About Freedom” and ghetto conscious “Concrete Reservation” sealed the album’s political bonafides. “Right On,” “Together Forever,” “Come Together,” and “Black Balloons” are positively uplifting, forming their own pot of gold at the end of a grayscale rainbow.

Fifty years later, Is It Because I’m Black is still as relevant as the day of it’s release. No liner notes. No extra tracks. Just the greatest Black concept album of all time.

Fifty years later, Is It Because I’m Black is still as relevant as the day of it’s release. No liner notes. No extra tracks. Just the greatest Black concept album of all time.

Ten years into his role as poster boy for pop soul and peak-hour R&B, Syl Johnson did an unlikely about-face and cut the most inspiring and powerful song he’d ever touch. “I didn’t want to write no song about hating this people or hating that people,” Johnson said. “I really didn’t have no vendetta against people. It’s a sympathy song.” Issued on 45 in September of 1969, “Is It Because I’m Black” struck an immediate chord within the black community, forcing the song up the charts by sheer volume of call-in requests. It would be Syl’s biggest hit for Twinight, climbing as high as #11 on the Billboard R&B chart during its 14-week stay, marking the defining moment of what had become more than just an occupation. Syl had his hands on a career.

The days of shuckin’ and jivin’ through dance songs were over, replaced by a heavy and sometimes cynical undertone that would dominate Syl’s output for the foreseeable future. As the world-at-large was changing, so was Syl’s personal life. Fed up with 13 years of her husband’s life-on-the-road, Hazel Thompson checked out of their bungalow at 6843 S. Aberdeen. The formerly rock-solid band was beginning to show cracks too, as the pressures of an offstage life took their toll. Willie Henderson was the first to duck out, grabbing his shot at producing Tyrone Davis for Brunswick. “It kind of fell apart,” Syl lamented. “Zachary became an entrepreneur. George Moss couldn’t travel. Harvey Burton was teaching school. And Cameron couldn’t go on the road. His wife wouldn’t let him.” For the first time in 33 years, Syl Johnson found himself alone. He holed up at Twinight’s woodshedding studio at 2131 S. Michigan (the former address of both King and USA Records) and spent the bulk of 1969 tinkering. That storefront space would host the rehearsal of several Johnson productions, before Syl made an 11-door journey north to Chess’s Ter-Mar studios, where many of his Twinight records, and those of others, were ultimately set to tape. But first he had to find a new band.

Seven blocks north of Ter-Mar, Brunswick's Jalynne Sound house band was feeling awfully underappreciated at the hands of A&R director Carl Davis. Davis had put the group together piecemeal after walking out of OKeh in 1965, installing Bernard Reed on bass, guitarist John Bishop, trumpeter Michael Davis, alto saxist Jerry Wilson, and drummer Hal “Heavy” Nesbitt. Jalynne Productions set up shop at Roosevelt and Wabash, housing Davis’ publishing and managing concerns, the latter of which boasted a stable of Gene Chandler, Otis Leavill, the Opals, Major Lance, Billy Butler, and Walter Jackson. When Jackie Wilson showed up at Jalynne, looking for a hit to revive his faltering career, everything changed. Following Wilson’s success with the Barbara Acklin/Eugene Record penned “Whispers” for Brunswick in 1966, Davis leveraged his new job at the label to set up a Jalynne writing workshop and studio in the old Vee-Jay offices at 1449 S. Michigan. The group would be used on many Brunswick and Dakar recordings between 1967 and 1969. But they were most egregiously offended at being left off the credits on Young-Holt Unlimited’s “Soulful Strut” (when, in fact, neither Eldee Young nor Isaac “Red” Holt had even played on the Top 5 Pop hit).

The days of shuckin’ and jivin’ through dance songs were over, replaced by a heavy and sometimes cynical undertone that would dominate Syl’s output for the foreseeable future. As the world-at-large was changing, so was Syl’s personal life. Fed up with 13 years of her husband’s life-on-the-road, Hazel Thompson checked out of their bungalow at 6843 S. Aberdeen. The formerly rock-solid band was beginning to show cracks too, as the pressures of an offstage life took their toll. Willie Henderson was the first to duck out, grabbing his shot at producing Tyrone Davis for Brunswick. “It kind of fell apart,” Syl lamented. “Zachary became an entrepreneur. George Moss couldn’t travel. Harvey Burton was teaching school. And Cameron couldn’t go on the road. His wife wouldn’t let him.” For the first time in 33 years, Syl Johnson found himself alone. He holed up at Twinight’s woodshedding studio at 2131 S. Michigan (the former address of both King and USA Records) and spent the bulk of 1969 tinkering. That storefront space would host the rehearsal of several Johnson productions, before Syl made an 11-door journey north to Chess’s Ter-Mar studios, where many of his Twinight records, and those of others, were ultimately set to tape. But first he had to find a new band.

Seven blocks north of Ter-Mar, Brunswick's Jalynne Sound house band was feeling awfully underappreciated at the hands of A&R director Carl Davis. Davis had put the group together piecemeal after walking out of OKeh in 1965, installing Bernard Reed on bass, guitarist John Bishop, trumpeter Michael Davis, alto saxist Jerry Wilson, and drummer Hal “Heavy” Nesbitt. Jalynne Productions set up shop at Roosevelt and Wabash, housing Davis’ publishing and managing concerns, the latter of which boasted a stable of Gene Chandler, Otis Leavill, the Opals, Major Lance, Billy Butler, and Walter Jackson. When Jackie Wilson showed up at Jalynne, looking for a hit to revive his faltering career, everything changed. Following Wilson’s success with the Barbara Acklin/Eugene Record penned “Whispers” for Brunswick in 1966, Davis leveraged his new job at the label to set up a Jalynne writing workshop and studio in the old Vee-Jay offices at 1449 S. Michigan. The group would be used on many Brunswick and Dakar recordings between 1967 and 1969. But they were most egregiously offended at being left off the credits on Young-Holt Unlimited’s “Soulful Strut” (when, in fact, neither Eldee Young nor Isaac “Red” Holt had even played on the Top 5 Pop hit).

Bassist Bernard Reed recalls Jalynne’s acrimonious split with Brunswick:

“I was a little disillusioned with how things were going for me down there. So we left Brunswick, and we got downstairs, and Jerry Wilson, the horn player, he said, ‘Well, hey, Syl Johnson is right up the street. We can go down there and talk to him. I know he’s looking for a band.’ And that’s what we did. We walked down the street to Syl’s place. He was right across the street from Chess Records then. We were on Record Row. Syl had a little rehearsal studio there set up. He wasn’t doing any major recording, but he had a machine there where we could make little dubs of what we wrote. Syl let us come in in the mornings, and we’d stay there up until the late hours of the night, practicing and performing new songs and putting together our own act. We dropped the Jalynne Sounds when we left Brunswick, I came up with the name Pieces of Peace. It just came to me as sort of a play on words. It was during that whole era—peace, flower power, during the end of the ’60s. It sounded good to me, and I mentioned it to the fellows, and they said, ‘Well, that’s who we are now! The Pieces of Peace!’”

“I was a little disillusioned with how things were going for me down there. So we left Brunswick, and we got downstairs, and Jerry Wilson, the horn player, he said, ‘Well, hey, Syl Johnson is right up the street. We can go down there and talk to him. I know he’s looking for a band.’ And that’s what we did. We walked down the street to Syl’s place. He was right across the street from Chess Records then. We were on Record Row. Syl had a little rehearsal studio there set up. He wasn’t doing any major recording, but he had a machine there where we could make little dubs of what we wrote. Syl let us come in in the mornings, and we’d stay there up until the late hours of the night, practicing and performing new songs and putting together our own act. We dropped the Jalynne Sounds when we left Brunswick, I came up with the name Pieces of Peace. It just came to me as sort of a play on words. It was during that whole era—peace, flower power, during the end of the ’60s. It sounded good to me, and I mentioned it to the fellows, and they said, ‘Well, that’s who we are now! The Pieces of Peace!’”

Syl put the Pieces of Peace rhythm section to work immediately, employing Reed, Bishop, and Nesbitt on the no-frills “Is It Because I’m Black.” Before the single even hit the streets, much less the charts, the full band was marked present on the Dynamic Tints’ Reed-composed “Package of Love Pt. 1 & 2” and had backed up Syl up on a handful of regional dates. With no one waiting at home and a band with nowhere else to go, Syl worked tirelessly rehearsing his next opus, an album of songs reflective of the changing times. With “Is It Because I’m Black” still bolding the pages of Billboard, the coming LP’s title appeared to Syl plain as day—or, in this case, black as night.

Issued in April 1970—a full 13 months before Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On—Is It Because I’m Black can rightly be called the first black concept album, a distinction few give it credit for. But that factoid, whatever its meaning then or now, failed to inspire music buyers: Johnson’s record never got a whiff of the two million copies Gaye’s did in its first year of availability. Syl lays the blame squarely on the record’s lack of marketability to a white audience:

“That was a college record. Black college kids. They’re political. But these kind of records tend to hurt you a bit. You’ve got white people, and then you’ve got white liberals. But you’ve got white people who care nothing about you talking about being black. They say ‘Why shouldn’t I sing “Is It Because I’m White”?’ They just don’t care for it. Not that they hate it, but they’re not going to pay five or six dollars to buy an album of it.”

Issued in April 1970—a full 13 months before Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On—Is It Because I’m Black can rightly be called the first black concept album, a distinction few give it credit for. But that factoid, whatever its meaning then or now, failed to inspire music buyers: Johnson’s record never got a whiff of the two million copies Gaye’s did in its first year of availability. Syl lays the blame squarely on the record’s lack of marketability to a white audience:

“That was a college record. Black college kids. They’re political. But these kind of records tend to hurt you a bit. You’ve got white people, and then you’ve got white liberals. But you’ve got white people who care nothing about you talking about being black. They say ‘Why shouldn’t I sing “Is It Because I’m White”?’ They just don’t care for it. Not that they hate it, but they’re not going to pay five or six dollars to buy an album of it.”

The album’s cover didn’t exactly move units either. Photographer Jerry Griffith dragged Syl to a burned-out building on 43rd Street to shoot the back cover image, and he finger-painted the iconic title over a stock photo of an eroding brick wall. The title track, coupled with the politically charged “I’m Talking About Freedom” and ghetto conscious “Concrete Reservation” sealed the album’s cool reception as the work of an “angry black man.” Which is unfortunate, as “Together Forever,” “Come Together,” and “Black Balloons” are positively uplifting, forming their own pot of gold at the end of a grayscale rainbow. The album’s closer burns the brightest. “Right On” devolves into a full-on party track, ending with Syl riffing on the line “I’m gonna keep on doing my thing,” as if to answer his critics before their needles reached the run-out groove.

Share