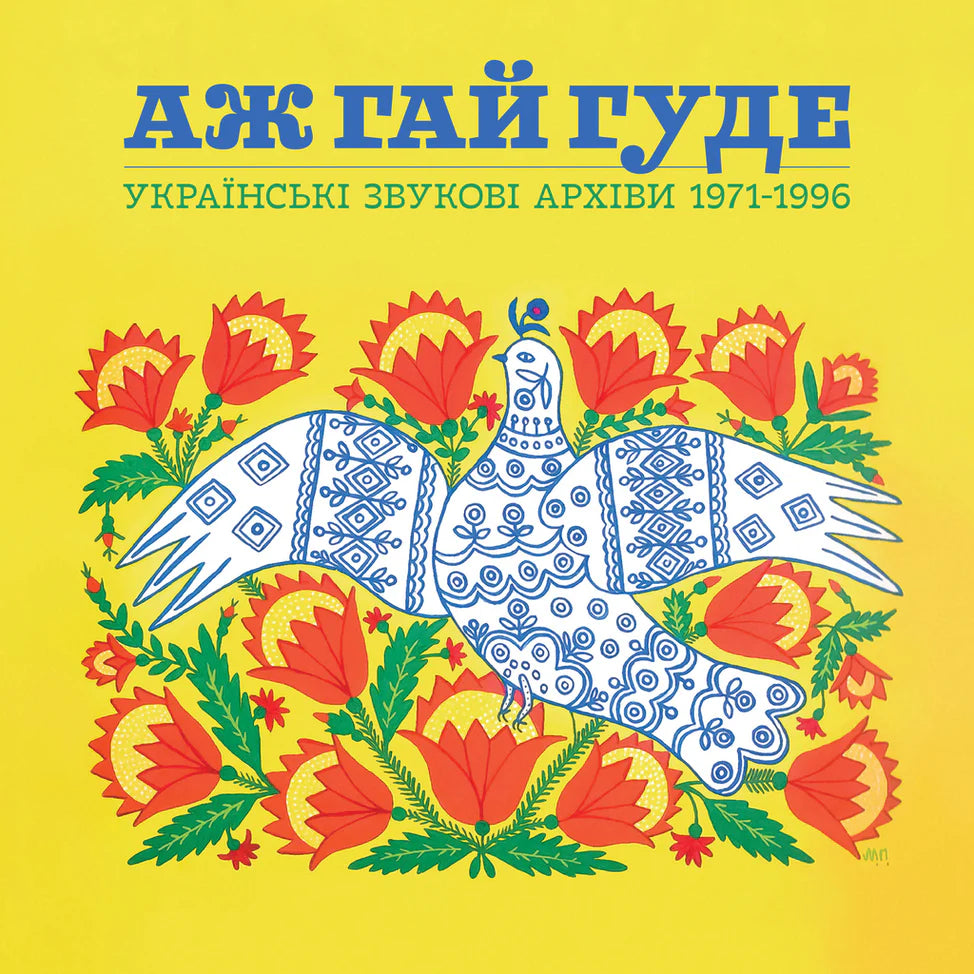

Even the Forest Hums: Ukrainian Sonic Archives 1971-1996 (LP Clear Sky Blue & Sunflower Yellow)

No se pudo cargar la disponibilidad de retiro

Light in the Attic Records proudly presents Even the Forest Hums: Ukrainian Sonic Archives 1971-1996—the first comprehensive collection of Ukrainian music recorded prior to, and immediately following, the USSR’s collapse. From subtly dissenting Soviet-era singles to DIY recordings from Kyiv’s vibrant underground scene, the compilation chronicles the development of Ukraine’s rich musical landscape through rare folk, rock, jazz, and electronic recordings.

“This record is a labor of love and a long time coming,” says label owner Matt Sullivan. Over the course of the last five years, Sullivan, alongside producers David Mas ("DBGO”), Mark “Frosty” McNeill, and Ukrainian label Shukai Records worked tirelessly to compile a carefully curated, chronological playlist. But behind the scenes, ongoing war & politics would shape the evolution of the tracklist, which originally featured both Ukrainian and Russian artists. “We found ourselves in the midst of a larger political issue; what began as a broader overview of a sonically underrepresented region suddenly became quite the controversial project,” Sullivan continues, “so we decided to pivot and focus only on Ukrainian music. There were times when it felt impossible to bring this project to fruition, so to be sharing it with the world today is truly humbling and long overdue.”

Guiding listeners through the physical editions of the album are insightful liner notes and track-by-track details by Vitalii “Bard” Bardetskyi—a Kyiv-based filmmaker, DJ, and writer. The 2xLP is housed in a beautiful gatefold package showcasing Ukrainian artist Maria Prymachenko’s beloved and iconic folk paintings. The vinyl edition features a 20-page booklet with artist photos & liner notes in both English and Ukrainian, pressed on Clear Blue Sky & Sunflower Yellow wax; the CD edition features bonus content housed in a deluxe, 64-page hardbound book.

Light in the Attic will donate a portion of proceeds directly to Livyj Bereh, a Kyiv-based volunteer group working to rebuild in the regions affected by ongoing war in Ukraine.

“Music has always pulled Ukrainians out of the abyss,” writes Vitalii “Bard” Bardetskyi in his liner notes for Even the Forest Hums: Ukrainian Sonic Archives 1971-1996. “When there is no hope for the future, there is still music. At such moments, the whole nation resonates under a groove. Music, breaking through the concrete of various colonial systems, is an incredible, often illogical, way to preserve dignity.”

While the songs collected in Even the Forest Hums were recorded during periods of immense societal and political upheaval—and certainly reflect the resilience of the Ukrainian people—they are rooted in the universal spirit of exploration: from post-war teenagers seeking fresh rhythms and artists experimenting with DIY recording technologies to an entire nation being introduced to decades-worth of previously-embargoed albums. Yet, until now, it has been nearly impossible for anyone outside Ukraine to explore the country’s flourishing music scene for themselves.

Much of this can be attributed to Soviet-era restrictions. Music, much like any other commodity, was tightly controlled before the fall of communism. “Only state-authorized performers who had gone through hellish rounds of the permit system could record at the few monopolistic, state-run studios,” explains Bardetskyi. While many of these compositions were released and performed to mass audiences, however, they weren’t necessarily what they seemed. “Some of the artists managed, even under difficult ideological circumstances, to build a whole aesthetic platform which was essentially anti-Soviet.”

Bands could slide under the radar by changing the lyrics of rock songs to reflect Soviet ideals or by performing traditional folk music with subtle outside influences. “This resulted in a whole scene that combined central-eastern Ukrainian vocal polyphony, Carpathian rhythms, and overseas grooves,” writes Bardetskyi, who refers to this era of music as “Mustache Funk.”

Examples featured in Even the Forest Hums... include 1971’s “Bunny” by Kobza. While the folk-rock group was known for their polyphonic vocals, this particular composition is an instrumental waltz, which blends elements of traditional Ukrainian music with progressive rock, British beat, and jazz-rock. Another example of “Mustache Funk” comes from the latter half of the decade, with the Caribbean-influenced “Remembrance” by Vodohrai. While the group—which included some of the best jazz musicians in the country—had a multitude of traditional hits, inspired jams like this one could, for a lucky few, occasionally be heard live.

While the 70s proved to be a golden age for Ukrainian music (complete with pop stars, large-scale tours, and legions of adoring fans), the excitement was short-lived. “The Soviet system finally understood that funkified beats quite strongly contradict[ed] [its] principles,” notes Bardetskyi, who adds that by the 80s, “The once prolific scene was almost completely colonized, appropriated, and largely Russified; the state radio and TV waves were occupied by banal VIAs and cheezy schlager singers.”

With tighter restrictions, however, came the rise of the underground. While the decade leading up to Ukraine’s independence was marked by great turmoil—including the political reform of Perestroika in the USSR and the Chernobyl disaster—it also marked a time of incredible creativity.

Mirroring global trends, the first half of the decade found many composers and producers experimenting with electronic music. Among them was Vadym Khrapachov, whose scores have appeared in over 100 films. His moody, Moroder-esque “Dance” (written for Roman Balaian’s iconic 1983 film, Flights in Dreams and Reality) is notable in that it was recorded on the USSR’s only existing British EMS Synthi 100 synthesizer.

Producer Kyrylo Stetsenko, meanwhile, was reimagining traditional songs for the dancefloor. Among them is 1980’s “Play, the Violin, Play,” by Ukrainian pop star Tetiana Kocherhina. Stetsenko, who produced the album for Kocherhina, created a hypnotic remix of the folk tune that was fit for a disco. Stetsenko is also featured here with 1987’s “Oh, how, how?,” in which he transforms a melancholic ballad by Natalia Gura into a synth-forward, breakbeat jam.

As the fall of communism approached, the scene continued to diversify—particularly as music from around the world became increasingly available. Kyiv, in particular, became an epicenter of creativity. In the early days, bands like Krok offered a preview of what was to come. Described by Bardetskyi as “The first real Kyiv supergroup,” Krok was led by guitarist Volodymyr Khodzytskyi and featured musicians from local Beat bands. In addition to backing the biggest pop acts of the day, the versatile collective explored a spectrum of styles in their own recordings, including fusion and electro-funk. They are represented here with the mellow “Breath of Night Kyiv.”

By the late 80s, Kyiv “was buzzing like a beehive,” recalls Bardetskyi. “It was a period of very active socialization and exchange of musical information and ideas; local musicians evolved with supersonic speed, absorbing decades of the world's musical background and transforming it into their sound.” While rock bands comprised much of this era’s first wave, artists continued to expand their repertoire as new influences pervaded the scene. The global rise of DIY recording technology and electronic instrumentation, meanwhile, also contributed to the growing sonic landscape.

Highlights from this period include the avant-garde improvisations of violinist Valentina Goncharova. Recordings like 1989’s “Silence” were created by a series of layered tracks and custom pickups. Similarly, composer Iury Lech paints a warm ambient soundscape with 1990’s “Barreras.” On the other end of the spectrum is the industrial “90” by Radiodelo (the project of Ivan Moskalenko—aka DJ Derbastler), which combines frenetic drum machine beats and haunting, reverb-soaked instrumentation. Post-punk was also thriving, with acts like Yarn (a large, loosely based collective) dominating the scene. “The interests of [Yarn’s] members extended all the way to medieval chamber music, which would clearly be noticeable in ‘Viella,’” writes Bardetskyi. The track features two of Yarn’s co-founding members: multi-instrumentalist and graphic designer Oleksander Yurchenko (who became a significant figure in modern Ukrainian music) and Ivan Moskalenko. Yurchenko is also represented here as part of Omi, a parallel project by the chart-topping electronic group, Blemish. 1994’s dramatic “Transference” (which features contributions by legendary Japanese musician Ryuichi Sakamoto and American singer-songwriter Diamanda Galas) serves up horror-movie-soundtrack vibes, particularly with the addition of eerie vocalizations.

Cukor Bila Smert’ (which translates to “Sugar White Death”) were also major players in the Kyiv underground. Interestingly, Bardetskyi notes, “In the reality of the general dominance of post-punk, the aesthetic message of Cukor Bila Smert’ was countercultural to the countercultural process itself.” For their contribution to the compilation, the experimental quartet provides 1995’s “Cool, Shining.”

In the years following Ukraine’s independence, Kyiv’s underground scene continued to flourish, particularly as Western trends became more accessible and Ukrainians found themselves at the forefront of their own cultural output. While the country’s music would largely evolve in new directions throughout the 90s, the final entry on Even the Forest Hums... provides a glimpse at what the future held. The album closes with 1996’s “Lion,” by Belarusian transplant German Popov, whose project, Marble Sleeves, was “one of the few Kyiv formations that tried to master jungle/drum-n-bass,” per Bardetskyi.

Though this compilation only scratches the surface of Ukraine’s vast and diverse music scene, Even the Forest Hums offers an in-depth overview of a significant period in the country’s cultural history and unites a number of influential figures in the same collection for the first time. As Ukrainian artist Oleksandr Schegel writes in the foreword, “This is our Ukrainian treasure. It is impossible to lose and impossible to win.”

Share